• 25th Anniversary Book Design: Strangers in the Land: The Ukrainian Presence in Cape Breton, by John Huk

_____________________________________________________________________________

OTHER WRITING

• ‘Finding a Fit: Wearing My Ukrainian Heritage in the Canadian Landscape’ ~ originally written for Canada’s 150th anniversary, as a member of the Professional Writers’ Association of Canada, 2017

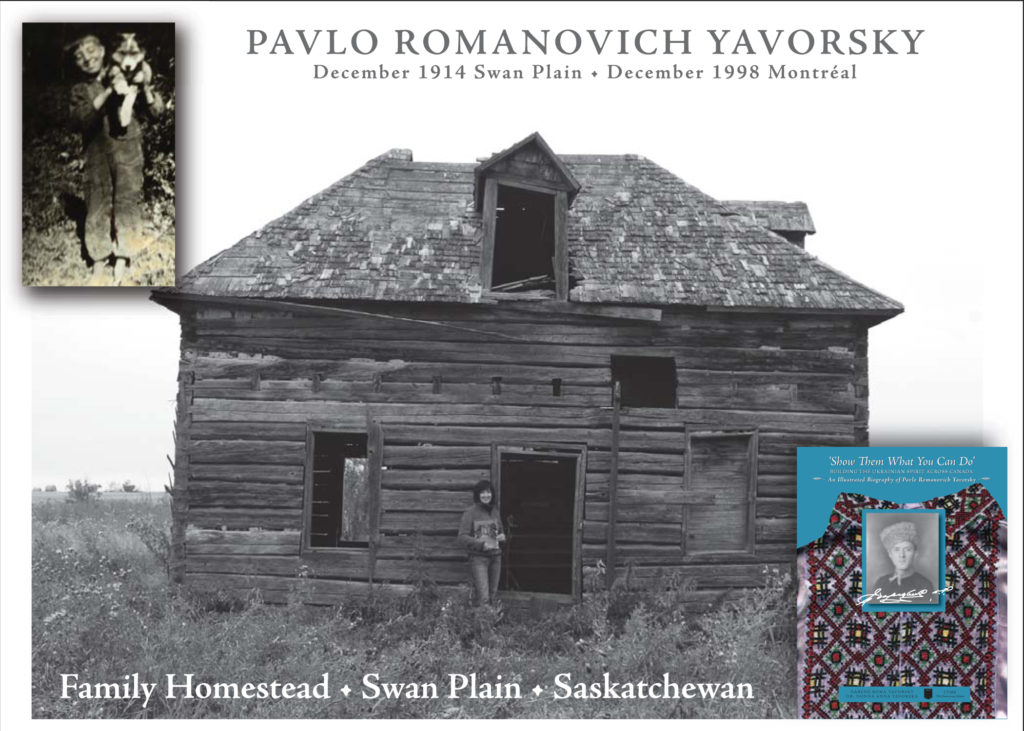

My father, Pavlo Romanovich Yavorsky, was born in Swan Plain, Saskatchewan in 1914. His parents had been among the wave of Ukrainians who emigrated to a bloc settlement in the prairies, the result of an immigration policy enacted to pioneer Canada’s west. While these ethnic neighbourhoods offered the advantage of living among others with familiar customs, language and circum stances, they isolated pioneers into groups — ultimately, targets of discrimination, particularly in 1914 when the First World War erupted and these new Ukrainian-Canadians were viewed with hostility as descendants of the Austro-Hungarian Empire: the enemy.

That year — clouded by the repressive atmosphere felt by new immigrants across the nation — was the year my father was born, the sixth child in a family that would eventually total 14, living in the hand-built house you see in the photo above. Before his tenth birthday, his father died. His mother was incapacitated by muscular dystrophy; she directed her children in planting the garden, calling through the open window from her bed near the cookstove.

My cousin Minnie, our family historian, wrote, “Roman passed away in August, 1924, leaving a widow with twelve children to struggle and sustain themselves, the youngest being only eight months old… The widow’s love for family and faith in God kept the family together rather than have some of the children given up for adoption.”

As a child, my father was inspired by his mother’s stories of the beauty of his ancestral homeland, and by his teacher who stayed after school to teach Ukrainian songs. Through these songs and stories, he nurtured deep feelings for his heritage that rose above the humiliation of ethnic slurs. Music, dance and literature lived in his imagination; hunger and deprivation, while constantly present, did not seem to preoccupy him. As a youngster, he was grateful to the nearby First Nations neighbours for sharing their food and survival skills. Yet the hunger he seemed to feel most sharply was to travel beyond his familiar landscape, as far as he could go.

He left home at the age of 14, closing the door on farming as his future. How is not known, but he learned to play mandolin, dance, write, become well-read and well-versed in history, geography and current events, speak several languages, be a diligent student, an inspiring teacher and engaging communicator.

At 17, he attracted the attention of the Ukrainian Self-Reliance League of Canada, which was working to form a national group for Ukrainian Orthodox youth. Rector Lukianchuk wrote to his colleagues:

“…I have briefly described how this boy, still young, is caught up with our ideal and is doing national work. He has the capacity to be a leader and he could become a good orator. For this reason, I would recommend to you that you admit him to the Institute for this winter… I guarantee that this boy has talent, if given the chance.”

So it was that my father, still a teenager, was engaged as a national organizer of Ukrainian-Canadian youth. In his memoirs, sixty years later, he recorded:

“My modest work as CYMK organizer began on September 25, 1932, when, in…Norquay, Saskatchewan, I organized Branch 19, in the name of General Volodymyr Sikevich… [N]o one paid any recompense or travel costs. What was needed was to have a vision, an unflagging commitment and an inclination to travel…

Having arrived at a given site, it was first necessary to give a speech on a suitable topic and so motivate the youth to join the organization. Usually I stayed in a location for two weeks. Every evening, I taught Ukrainian folk dancing and prepared a concert performance for the end of my stay… Every evening at rehearsals of dancing, singing and recitations, the hall was filled to capacity with older parishioners who watched their children being taught ~ thus preserving the national heritage of their famous Cossack ancestors! Ukrainian dances became the impetus behind the revival of Ukrainian folk dress. Ukrainian embroidery began to reappear and became the pride of Ukrainian children born far from beloved Ukraine, in the wide open spaces of Canada…”

He visited ten more Saskatchewan locations before the year was over, founding branches in each. Early in the new year (1933), he was called to Edmonton, and assigned the task of organizing branches across Alberta. Upon his departure, he was told, “Go into the province and show what you can do.”

Showing what he could do amounted to a great deal, that year and those that followed. Despite many hardships, he maintained a cheerful outlook; characteristically resilient, optimistic, sensitive and generous. He forged countless friendships and was grateful for unexpected kindnesses from the many people who billeted him in his travels. The good experiences shaped his character. His innate creativity flowed from his heritage, with its fine traditions of music, dance and poetry, which he believed were enriching contributions to Canadian society.

“We brought valuable treasure: Ukrainian dance, the word of [national poet] Shevchenko and the songs of the native land into every corner of Canada… For youth, born in the free, new land of Canada – this is native land! We built our life with the thought of living together with our neighbours, to build Canada and to feel that there was no other loyalty…”

From the ages of 17 to 22, my father travelled across Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba and Ontario, setting up CYMK branches, teaching Ukrainian dance, organizing concerts, performances and conventions. By the end of 1937, CYMK had 6,500 members in 168 locals. In the fall, before his 23rd birthday and as a result of his own initiative, he received a mandate to represent the film company of Vasile Avramenko, collecting funds toward the production of ‘Cossacks in Exile’. Ultimately, his position expanded to include media liaison, public relations, dance instructor, co-script-writer and performer of multiple roles in the film. By 1939, he was organizing classes in Ukrainian folk ballet and directing performances in Vancouver, Edmonton, Toronto and points in between … eventually reaching Sydney, Nova Scotia, where the Ukrainian parish history states:

“Pavlo Yavorsky taught Ukrainian school and Ukrainian folk dancing until he left to join the Canadian Army. Mr. Yavorsky, in his short [3-year] stay in Sydney, instilled not only the children of the parish with a love for heritage, nationality and culture, but he also provided the spark in the older people… With his group of 30 dancers, Mr. Yavorsky gave concerts for the Red Cross, Festival Groups, and many private concerts as well. For years after he left, people still remembered the dance[s] which are continued to this day. Mr. Yavorsky had instilled love for their parish and helped the parish not only keep together but to grow.”

My father left the Maritimes in 1943 for Montréal, Québec, where his reputation in the newspapers as ‘artist balletmaster’ led to his participation as consultant and performer in ‘Ukrainian Dance’, a National Film Board of Canada production. He was 28, leading a Ukrainian dance school within St. Sophie Ukrainian Orthodox parish. One of his dance partners in the film was a parish member, whose sister, Leontina Pidwysotska, won my father’s heart. Ten years his junior, my mother later told me, “I had been reading about him in the newspaper since I was 12 years old – he was my hero!” They married in 1944, the same year my father passed the government exams and became a Canada Customs officer.

The young couple first lived in a lovely small flat, where my mother studied piano; then bought a duplex upstairs from her parents. Here, in St. Laurent, my sister was born in 1948, my brother in 1950 and finally, I arrived in 1953. Living in such close proximity to our grandparents caused more than a little friction at times; in 1956, our parents sought a larger home on their modest income — which they found on the developing south shore of Montréal. It was more than an hour away by public transit, not only from our relatives but also from the Ukrainian church and most of its parishioners. Our parents were active in church affairs (our mother being the daughter of one of St. Sophie’s founders), and as a family, we participated fully in the traditions of the Orthodox calendar, at church and at home.

For my siblings and me, growing up in Greenfield Park ~ going to school, playing outside, interacting with neighbours ~ was a world away from life inside our home. Speaking Ukrainian, preparing traditional dishes, observing religious holidays, saying our prayers every night with one of our parents watching over us all made perfect sense inside our home. The way we lived was who we were. Our appreciation for aesthetics and doing things with care seemed instinctive; we read books with beautiful pictures in them, listened to beautiful classical music from the Record-of-the-Month Club, made beautiful things (Ukrainian embroidery, Easter eggs, breads). We took piano lessons and studied hard to do our best. “Good, better, best; never let it rest, until your good is better, and your better is your best.” But outside, it was confusing, uncomfortable and often painful. Being made fun of for who we were was bewildering. The fact that all three of us got high marks in school didn’t help; it was one more reason for being ostracized.

There are different ways to survive. Mine was to retreat into debilitating shyness; as a young child, I would hide — in the closet, the bathroom, the basement. As an older child, I hid behind an outer self that tried to blend in, and later, as my artistic leanings developed, I hid behind a renegade personality that displayed more bravura than I felt.

For many years, I felt that who I was was contained within an ill-fitting costume. It was only with a very few that I could shed my disguise. Looking back over the intervening decades, I see that it takes the arc of one’s life to sift out the dross and occupy oneself with the things that really matter. I could appreciate my heritage and admire my parents for their wonderful qualities, as I got on with a varied career that kept as its constants the lessons they had taught me, not by word but by deed: attention to detail, thinking creatively, caring about quality and being respectful of and generous to others.

When my father passed away in 1998, I was living in Ontario, self-employed as a writer and graphic designer. I was certainly aware of his continued devotion to Ukrainian-Canadian affairs even in his last years, but had no idea of the scope of his accomplishments over his lifetime. A single event that occurred almost seven years later became a turning point, influencing not only my artistic endeavours but also my feelings about my identity as a Canadian with a Ukrainian background.

*** *** ***

In 2005, my mother received a telephone call from Irka Balan, who was curating a Canadian Heritage-sponsored travelling display titled Vasile Avramenko: A Legacy of Ukrainian Dance. In her research, Irka said, the name of Pavlo Yavorsky arose time and again. She knew of him for his association with CYMK and other Ukrainian organizations over the years, but was intrigued to be discovering glimpses of the depth of his involvement in introducing Ukrainian dance to far-flung western communities, in Avramenko’s dance schools and in the film, ‘Cossacks in Exile’. She knew so much more about my father than I did! Her questions prompted a search for answers through boxes of his papers and photo albums, and two trips to Ottawa to study the collections of documents he had donated, two decades earlier, to Library and Archives Canada.

I learned so much more about my father after his passing than I ever knew while he was alive. Not one to recite a litany of his achievements; he was the kind of father who neither lectured nor laid down the law. He was kind and caring, a soft touch for parental permission, told entertaining stories, and cooked and baked like a dream – something I never saw my friends’ fathers do. He never referred to ‘women’s work’ or ‘men’s work’; from his example I learned that there really was no such thing, since from a young age he had had to do whatever needed to be done.

In his extensive files, we found a treasure trove of fascinating material which became the basis for a set of biographical posters we prepared for Irka Balan’s exhibit. This family project planted the seeds of a larger endeavour: an illustrated biography of my father, published in 2007 — the 75th anniversary of CYMK — with support from the SUS Foundation of Canada. ‘Show Them What You Can Do’ – Building the Ukrainian Spirit Across Canada: An Illustrated Biography of Pavlo Romanovich Yavorsky was requested by libraries and institutions from coast to coast.

So far, I had not had to venture far out of my shell, other than a few communications with a representative of the sponsoring organization and a couple of meetings at the archives in Ottawa. My comfort zone was at my desk, writing and designing the book layout and, later, promotional materials for distribution by mail. I was not active in the Ukrainian community; I did not seek to join the nearest Ukrainian church; I only observed traditions at home and with family. The scars of childhood ran too deep; avoidance was my default.

But the publication of my father’s biography seemed to open floodgates of attention. I was contacted to submit a proposal to the Ukrainian-Canadian Congress which resulted in his being posthumously named a 2008 Saskatchewan Nation-Builder. My sister, brother and I accompanied our mother to the ceremony in Regina, where she accepted the award on his behalf. In 2009, I participated in an exhibition, ‘A Cape Breton Story of Ukrainian Dance … from Village to Stage’, curated by ethnomusicologist Dr. Marcia Ostashewski at the Cape Breton University Art Gallery. In 2010, we worked together again, this time on the exhibition, ‘Mnohaya lita! Celebrating 100 years of Ukrainian faith in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia’. In 2011, another collaboration involved the 25th anniversary republication of ‘Strangers in the Land: The Ukrainian Presence in Cape Breton’ by local historian John Huk who, as a child, had been one of the exceptional performers in my father’s dance group.

There have been other Ukrainian-themed projects that included some aspect of my father’s history, such as an exhibition with Dr. Ostashewski in 2015, in which she uncovered new information about his musical accomplishments as a self-taught violinist, composer and orchestral leader. One project after the other, I have had to overcome extreme anxiety in public appearances because now, in my father’s absence, they are opportunities to honour him.

With proceeds from sales of my father’s biography, I created a foundation in his name and established The Pavlo Romanovich Yavorsky Youth Award in Ukrainian Dance, presented at the Tavria Ukrainian Dance Festival in his home province of Saskatchewan to “the student whose solo performance communicates joy and passion for the art form, conveying the heart and soul of Ukrainian culture and tradition.”

The passage of time, learning from others, working hard to conquer fears and focusing on worthwhile actions have all helped to release, if not completely eradicate, previous strictures. Since my mother (who had her own compelling back story) passed away in 2013 after several difficult years’ struggle with dementia, I have missed both my parents — unbearably and increasingly, it seems. I remember them as good people with many gifts and few faults, courageous, compassionate and self-effacing. By their example, they raised my siblings and me to be ‘citizens of the world’, open to friendship with all nationalities and walks of life.

I attended a vigil at the Islamic Centre near my home in Kincardine last month [in 2017], in sympathy for the loss of life at the recent mosque attack in Québec. Afterward, those of us who had gathered outside for the candle-lit ceremony were invited in. The children served hot chocolate and sweets; everyone was so hospitable and appreciative of the support; one of the mothers hugged me when I went to say good-bye. The warm, welcoming atmosphere was in contrast to the chill that I felt in fearing for their safety. Would they be targeted here? Who would do such a thing? Why does it happen at all?

I love Canada. I love being Canadian. When I visit other countries, I am happy to declare myself a Canadian. As we mark Canada’s 150th anniversary this year, I know there will be an uplifting feeling, celebrating July 1st amid throngs of people unselfconsciously sporting goofy maple leaf hats or red-and-black plaid moose antlers. But the picture isn’t as clear as the sparkling waters of Georgian Bay; there are some murky depths lurking. The experience of being Canadian — whether born here or newly arrived — seems to depend so much on numbers. Who out-numbers whom? The stings of discrimination that I felt as a school kid in the ’60s haven’t faded much, and I still don’t understand why some people said or did those things. Curiosity about others, an interest in their lives and acceptance of our differences can lead to enriching experiences and lasting friendships: that’s what I learned at home. But outside, at school and elsewhere, I learned some other things the hard way.

I am glad that, one generation along, my nephew was able to bring schoolmates to my parents’ house for my father’s delicious varenyky which he faithfully prepared every Friday. I grew up in a time and place where that was not possible, much less appreciated.

Canada is a great country, full of beauty, incredible people, inspiring landscapes. It offers wondrous opportunity ~ if you can surmount or ignore some difficult obstacles and concentrate on fulfilling the dreams in your heart and imagination.

— 30 —